Michelle Concepción: Abstraction – Sensation

Frank, Peter. Volver, catalogue, 2008.

The power abstract painting holds over the beholder is not so much that of form itself but of its suggestion. The ideologies of artistic practice may motivate painters and fix their positions in the discourse of art history, but for viewers of the work itself, the painting exists as image and/or object-an image or object whose relationship to the quotidian world of perception is ambiguous and multivalent. Our associations frame our understandings: Frank Stella’s declaration that “What you see is what you see” may be a theoretical tautology, but when what you see is what you associate with what you are seeing-a process of recognition, that is, of discerning resemblances-an abstract form takes on resonance outside the control of its maker.

An interpretive responsibility thus befalls the beholder, acknowledged by Marcel Duchamp when he opined that “The viewer completes the work of art.” In her painterly practice, Michelle Concepción acknowledges this responsibility, and enters thereby into an ongoing relationship with the viewer. Rather than insist that all that is in her work is pigment assuming shapes on a support, Concepción amplifies the associative resonance of those shapes by manipulating the pigment-and, masterfully, the relationship of pigment to support. A painter of effect (although not merely a painter of effect), Concepción subjects a highly refined formal vocabulary to an intricate interplay of facture and illusion, luminescence and darkness, apparent volume and apparent transparency, color and colorlessness, surface and infinite gradation. Such an effect-driven interplay opens up a universe of comprehensions, none of which Concepción controls-and all of which she profoundly influences.

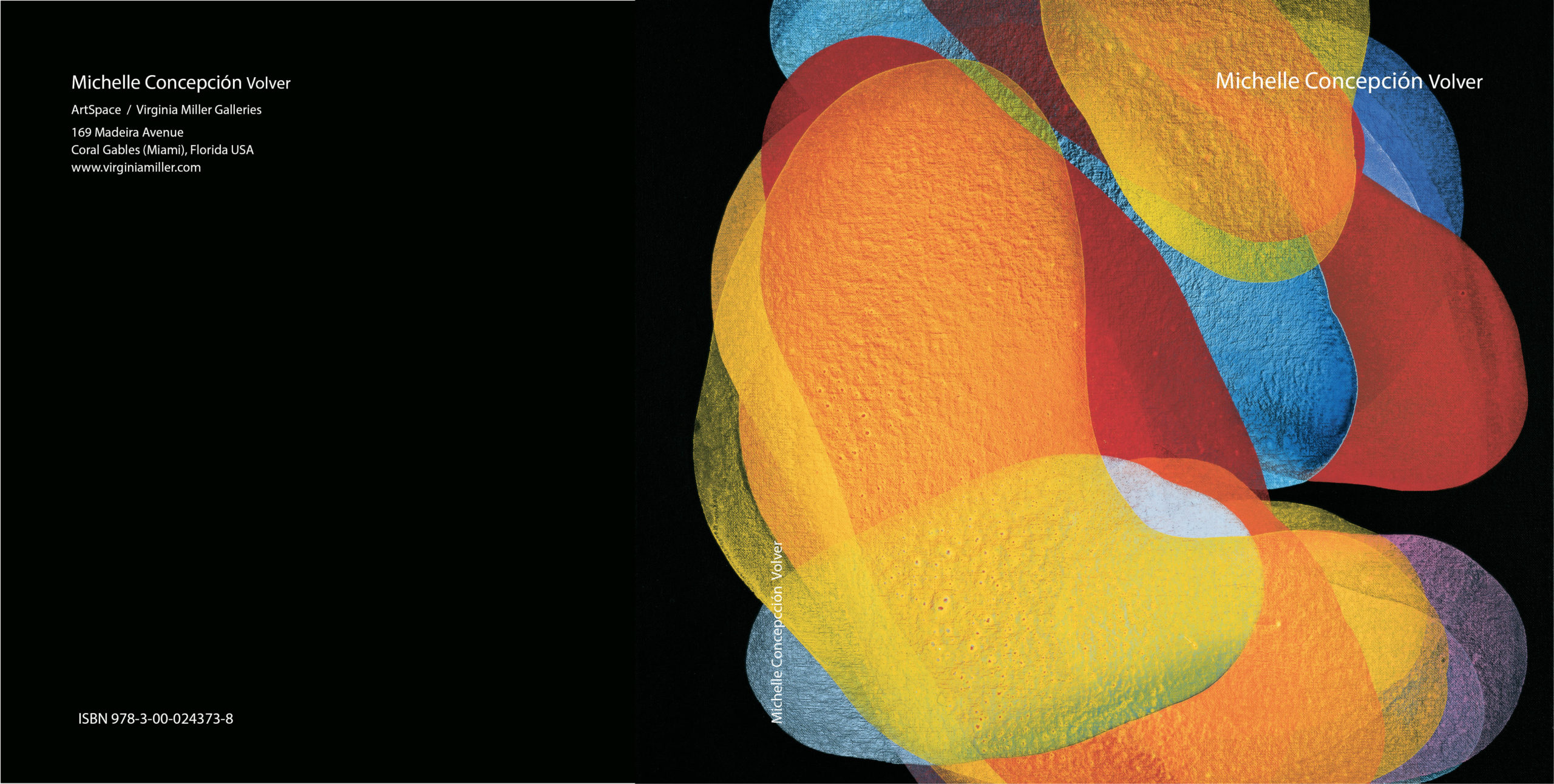

Each of us sees the myriad interplays of form, color, and shade that dominate Concepción’s paintings slightly differently, perhaps, but we all recognize that her forms float, often one across another, and that they occupy a neutral field that can be read at once as behind and amid her shapes. The nature of those forms is impossible to assert. Some of us see inorganic objects like stones or oil slicks, others of us discern microscopic organisms, still others read these blots and tendrils as plant forms (especially aquatic ones), and so forth. Some of us are certain these shapes, whatever they are, are in motion, while others among us see them fixed in the picture, even establishing patterned rhythms. The interpretive possibilities are manifold, but they remain just that: interpretive, not definitive, and possibilities, not actualities. If for Concepción the paintings are at least what they are made of, for us, not privy to her technique, not even this is fixed.

Gerhard Charles Rump has remarked that Concepción’s forms “show themselves to be a section of the world much larger than the extension of the canvas,” 1 and the tendency of the forms to repeat in most of her paintings until they pass out of the picture (continuing the microorganic metaphor, as anyone knows who has tried to frame a protozoan under the gaze of a microscope) bear out Rump’s observation. But equally, the nature of these paintings as image fields helps us retain a sense of the paintings as concretions, as things, meaning that on at least the level of material, the objecthood of any given painting confines its shapes to its surface; the shapes may imply a pictorial limitlessness, but ultimately they are subject to the traditional bounds of pictorial practice.

The poetics of Concepción’s art emerge from this web of artistic generation and audience reception, from the constant play between what has been made and what is perceived. But this play, this enmeshing of meaning, does not bind such poetics. Those finally anchor in what effect Concepción’s paintings have upon something behind our eyes. We do not feel lighter, brighter, smaller, larger, more enchanted, or more mystified because these works have fooled our eyes into reading them this way or that; we feel thus because these works are painted to convey such sensations. Their ability to trigger metaphors serves their ability to trigger feelings not the other way around. In the end, they are not pictures, but paintings-abstract paintings, meant to transcend the condition of images and provide instead the condition of sensations. To amend Stella, What you see is what you feel.

Perhaps it is not necessary to note that “sensations” and “feelings” do not connote “emotions.” Concepción’s art exists in a realm of expression at once more somatic and more conceptual than emotive. In this, her diaphanous plants, her floating worlds, her Magellanic Clouds-call them what you will-transport us not simply with their beauty, although they are capable of that, but with their various formal qualities. Their color, their grain, their patterning, their partial disembodiment, their suspension in some sort of fluid or humor-these and other plainly seen but not plainly felt factors conspire to commute sensations that beggar description.

The hundred-year history of abstract art is a history of distilling the ineffable. Whether motivated by intellectual argument or spiritual quest, the abstractionists in our midst have chosen not to depend on the recognizable world as a subject, although it remains available to them, and us, as a visual or conceptual armature; rather, it is the world inside their heads, and ours, they choose to elaborate. Michelle Concepción follows in the footsteps of Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian, Rothko, and a host of nonobjective painters who in their various ways have explored and conveyed what was at once deep inside them and all around them, visually inchoate but profoundly immediate in experience. When this auratic force emerges and coalesces, we tend to find the mundane world in such formulations. But even as we do, those formulations act upon us and within us. Concepción’s is an art not of things, but of their ghosts.