The Metaphysical Fairyland of Michelle

Goodeve, Thyrza Nichols. Logical paintings catalogue, 2017.

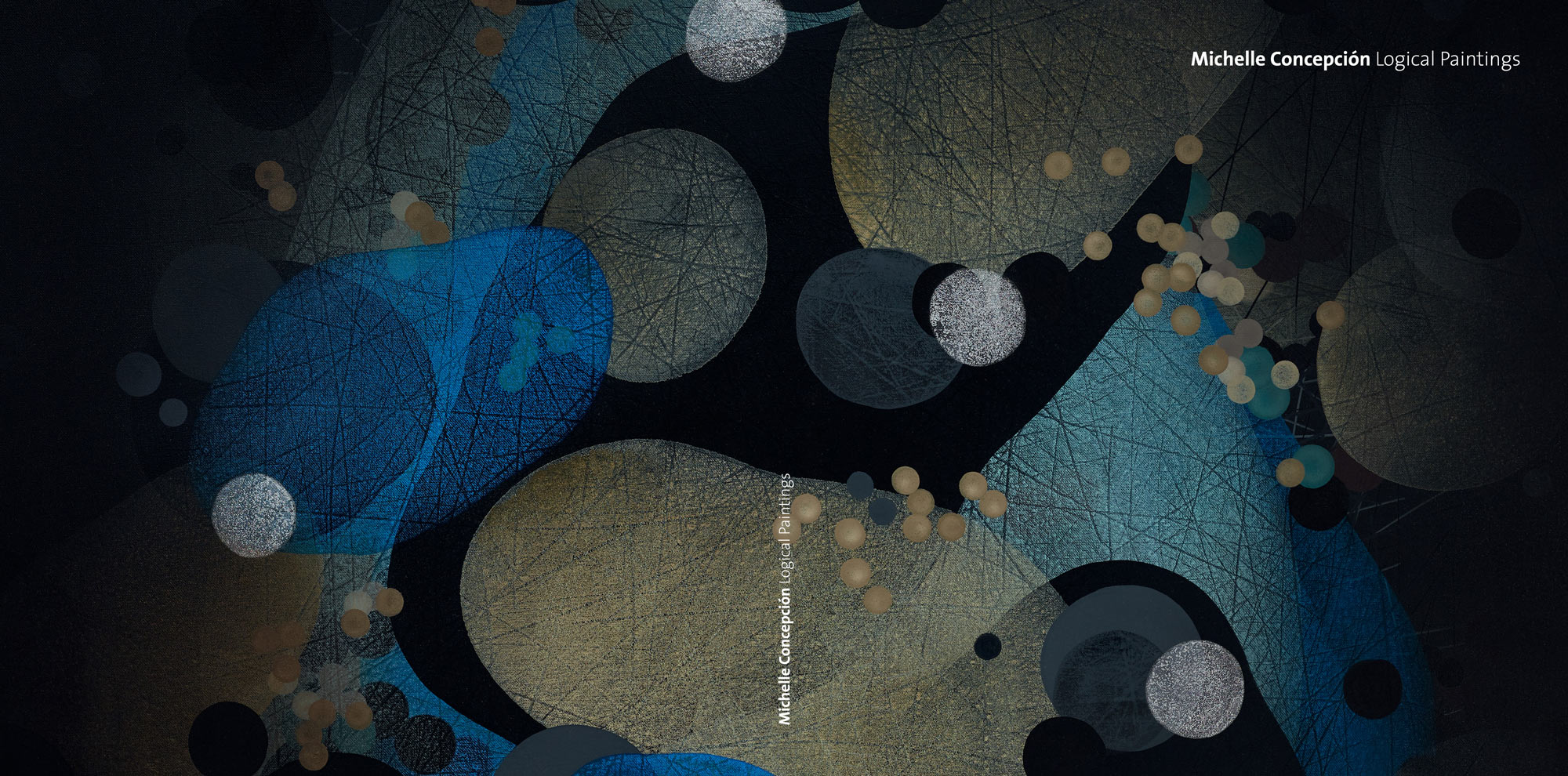

“Concepción’s is an art not of things, but of their ghosts.” 1When the friction and incongruities of the world overwhelmed me as a child, I would close my eyes and disappear into the world of torrential atmosphere that lived behind my eyes. When this happened, my body’s proprioception transferred from the sensation of a trunk connected by limbs, into a substance without mass, like light, an aqueous spirit animal or ghost, falling through space. A similar feeling comes over me when I look at Michelle Concepción’s paintings. Coordinates disappear as each canvas suggests a universe in motion, where color and scale have no measure except the size of one’s imagination. Black Pearl, 2016 could be as small as a cell seen under the power of a mega-microscope or as large as a galaxy that is so many millions of light years away as to be closer in time to the Big Bang than our 21st century.

Imagine we are Mr. A. Square from Edwin A. Abbott’s 1884 Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions landing in one of Concepción’s paintings. In his world, three dimensions are outlawed. In fact, his encounter with Mr. Sphere is reason enough for him to be accused of treason and imprisoned because it is sedition to acknowledge a logic beyond what a line or point can feel.

Behold yon miserable creature. That Point is a Being like ourselves, but confined to the non-dimensional Gulf. He is himself his own World, his own Universe; of any other than himself he can form no conception; he knows not Length, nor Breadth, nor Height, for he has had no experience of them; he has no cognizance even of the number Two; nor has he a thought of Plurality, for he is himself his One and All, being really Nothing.2

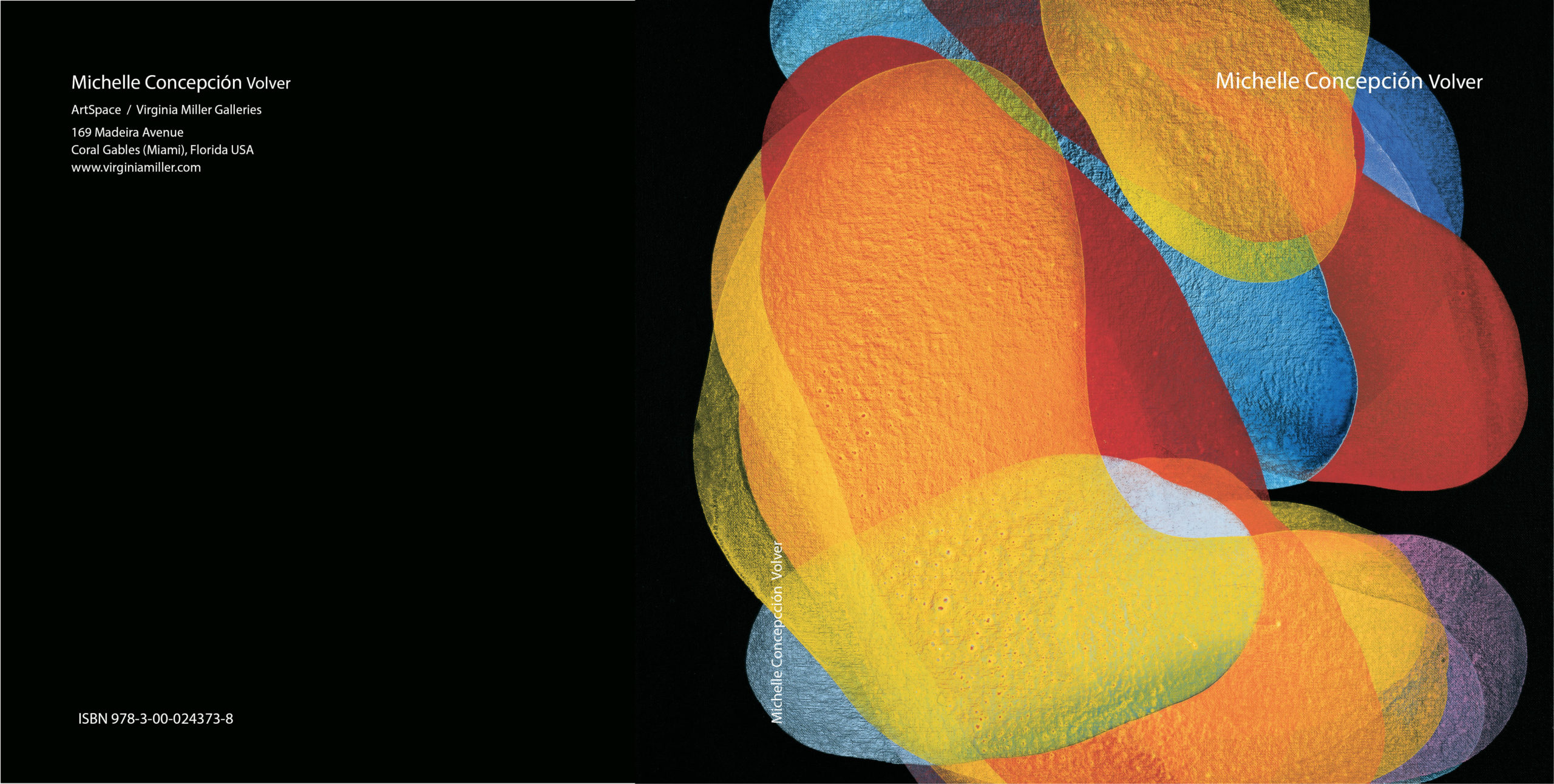

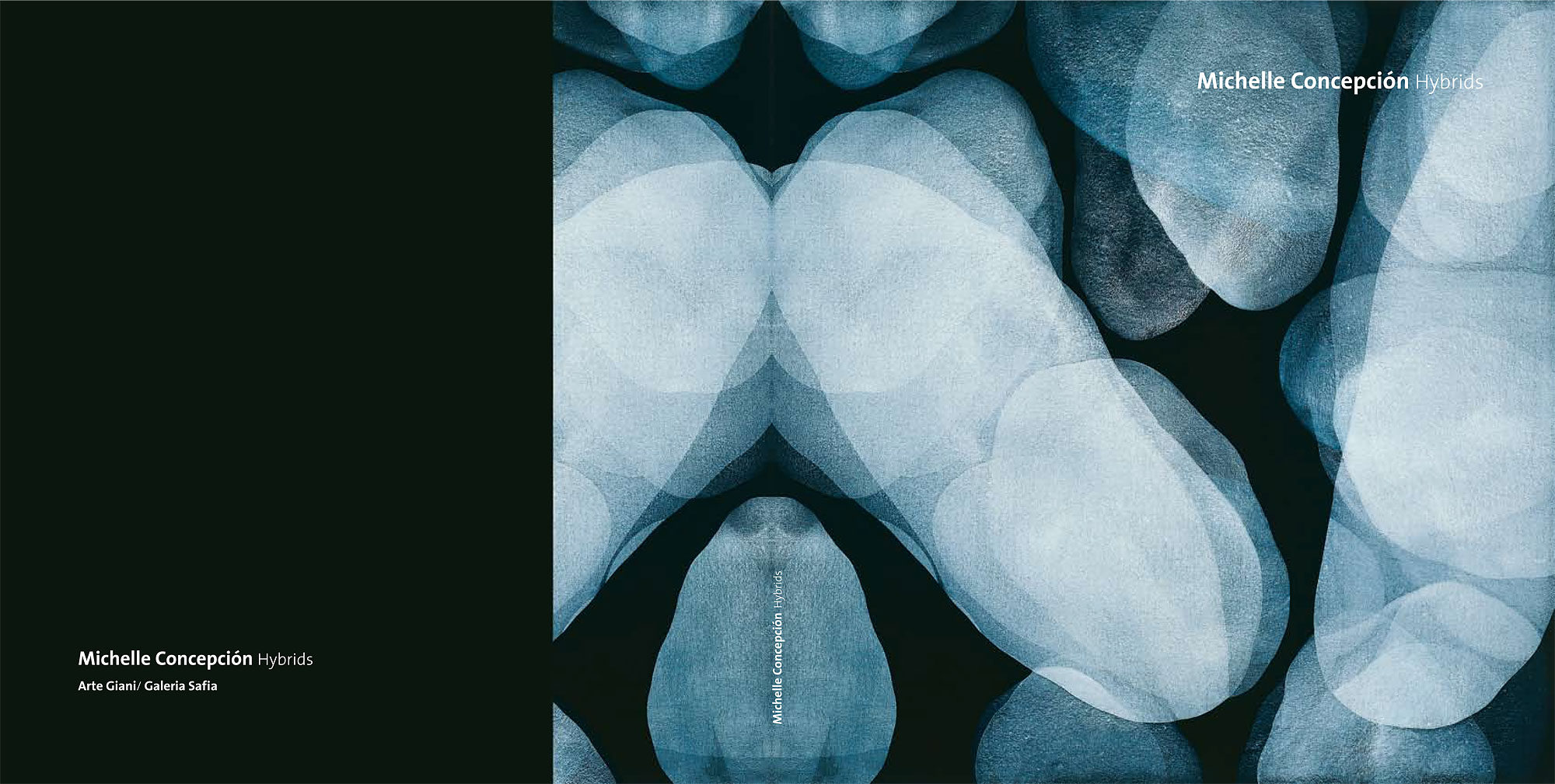

Not so for Michelle Concepción. In fact, if Mr. A. Square visited Night Painting, 2017 or Hybrid Fade, 2015, there would be no need for him to exchange law abiding behavior for his right to inhabit higher dimensions. As you can see solids do not block one another; shapes collect without being territorial because they have a presence, as wash, which suggests generosity. In En el jardin, 2017, or even the dense yet breathy Between the Lines 2, 2017, acrylic follows the logic of watercolor, an ontology of transparency, mutable and attentive to what is contingent. How many layers of being emerge when a palette of red, yellow, and green pass in and out of one another like sea creatures? Where does one shape begin and end when one can see a seeming infinite collection of layers, nested and nestled one on top of one another? How many substrata of time would be represented if each coat represented its own individual zone? What would Mr. Sphere say to this?

As I look at Before Night Falls, 2016 or Night Painting, 2017 I am reminded of what Walter Benjamin says about a photograph:

search such a picture for the tiny spark of contingency, of the here and now, with which reality has (so to speak) seared the subject, to find the inconspicuous spot where in the immediacy of that long-forgotten moment the future nests so eloquently that we, looking back, may rediscover it.3

Although nothing could be further from Concepción’s diaphanous aesthetic than the referential reverence of photography, her paintings, while wholly abstract, are defined by the logic of contingency unburdened by weight or territorial possessiveness. The interlocking layers of color, texture, paint, shape, and air seem to inhale and exhale into and out of one another, freed of mass or recognizable temporality. Yet, all is contingent, dependent on what it touches. As shapes hover and incorporate one another in Black and White Clusters, 2016 or Whimsical, 2017 their ontologies shift. How else to account for the many states of the white and grey translucent biomorphic blobs as they float across and interact with opaque black, like ghosts set in motion. Isn’t this what Peter Frank means when he says Concepción’s work “is not an art of things but ghosts”? For who has less patience for earthly dimensions than ghosts. They have their own logic of abstraction as they haunt and hover the living like Concepción’s biomorphic beings exist on several planes—porous yet scratched and crossed with marks. Texture is a kind of memory; geometry a logic of interaction. But within it all, I can not let go of the sense I am looking into time. After all, ghosts and Concepción’s paintings are accounts of being – in her case the ontology of abstraction.

In this sense Concepción is the arbiter of life-forces as much as she is a painter of color and shape. As she pulls her brush across the surface, or scratches at a line, what she is really doing is channeling the vital principle of each shape, line, swish, blotch, and pattern of textured color at the moment when it is most alive. The paintings are testaments or snapshots of the moment of their creation, where the shadows and specters—ghosts—which hover around them are allowed to come into view before passing away. This is not an aesthetic of competition aimed at who will win, but rather art as a metaphysical fairyland or allegory of existence, founded in painterly acts of generosity. In Black and White Clusters, 2016, or the more foreboding Night Painting, 2017, apparition and object exist in pools of potential rather than presence; zones of dimensionality shift before our eyes – no longer referencing the art historical space of mid 20th century abstraction but rather, like Klee or even Rothko, existence itself. Isn’t that what color, is, a consequence of wavelength; continuums of color made of photons whose signature property is, they have no mass. And isn’t this paradox of being at once present (as a body) and absent (lost within the metaphysical torrent of Concepción’s paintings) precisely what it’s like to be a ghost, or a visitor to a dimension we have yet to understand?